Every parent’s been there – watching another child the same age as yours doing something yours hasn’t managed yet, and immediately spiralling into worry about whether there’s a problem.

Developmental milestones are useful guidelines for tracking how children are progressing, but they’re also a source of endless anxiety when your child doesn’t hit them exactly on schedule. Here’s what you actually need to know about milestones.

What Milestones Actually Are

Developmental milestones are skills or behaviours that most children can do by a certain age. They cover physical development (gross and fine motor skills), cognitive development (thinking and problem-solving), language and communication, and social-emotional development.

The key word there is “most.” Milestones represent what typically developing children achieve within a certain age range, not rigid deadlines that every child must meet on exactly the same schedule.

There’s significant normal variation in when children hit different milestones. One child might walk at 10 months, another at 15 months – both can be completely normal. Some children talk early but walk late. Others are physically advanced but slower with language.

Milestones are better understood as ranges rather than fixed dates. When you see “walks independently by 12 months,” that’s an average, not a requirement.

Why Milestones Matter (And Why They Don’t)

Tracking developmental progress helps identify children who might benefit from early intervention for developmental delays or disorders. The earlier these issues are caught, the more effective intervention tends to be.

Conditions like autism, cerebral palsy, hearing or vision problems, and various developmental disorders often first become apparent through missed milestones or unusual developmental patterns.

So yes, milestones serve an important screening function.

But they’re also wielded like weapons in competitive parenting circles, creating anxiety where none is needed. Your baby rolling over a few weeks later than the neighbour’s baby means precisely nothing about their intelligence, future success, or your parenting quality.

The goal isn’t raising a child who hits every milestone weeks ahead of schedule. It’s identifying genuine delays that need assessment and support whilst maintaining perspective about normal variation.

Birth To 3 Months: The Fourth Trimester

Newborns are working on basic survival skills – eating, sleeping (sort of), adjusting to life outside the womb.

By 3 months, most babies can lift their head and chest when on their tummy, follow moving objects with their eyes, recognise familiar faces, and respond to loud sounds. They’re starting to smile socially rather than just reflexively, making cooing sounds, and bringing hands to their mouth.

Some newborn reflexes – like the Moro reflex where babies startle and throw their arms out – are actually developmental markers themselves. These reflexes should be present at birth and gradually disappear as the nervous system matures.

Concerns at this stage might include not responding to sounds, not following objects with eyes, very stiff or very floppy muscle tone, or not showing any interest in faces. But remember that babies develop at different rates even this early – some are alert and socially engaged from week one, others take longer to wake up to the world.

4-6 Months: Getting Interactive

This is when babies become noticeably more interactive and intentional. They’re rolling over (though timing varies – some roll at 4 months, others not until 6), supporting their weight on their legs when you hold them upright, and reaching for toys.

Language-wise, they’re babbling – making sounds like “ba-ba” or “da-da” without meaning attached yet. They’re responding to their name (eventually), laughing, and showing clear preferences for certain people or toys.

Fine motor skills are developing – they can grasp toys, transfer objects between hands, and are endlessly fascinated by their own hands and feet.

If a baby at 6 months isn’t showing any interest in reaching for objects, isn’t making any sounds, seems unable to support any weight on their legs, or isn’t showing recognition of familiar people, that warrants discussion with a health visitor or GP.

7-12 Months: Mobility Begins

This is the huge mobility phase. Some babies crawl at 6 months, others skip crawling entirely and go straight to walking. Some bum-shuffle instead of crawling. All of these patterns can be completely normal.

Most babies sit without support by 8-9 months, pull themselves to standing by 9-10 months, and take first steps somewhere between 10-15 months. But again, there’s wide variation.

Language development accelerates – they understand simple words and commands before they can say them. “No” and names of familiar objects get recognised even if they’re not yet speaking. First words typically emerge around 12 months, though some children don’t say anything recognisable until 15-18 months.

They’re developing object permanence – understanding that things exist even when hidden. This leads to endless games of peekaboo and dropping toys from high chairs to watch you retrieve them repeatedly.

Stranger anxiety often peaks during this period, which is developmentally normal even though it’s socially awkward.

Red flags at this age include no babbling or gesture use by 12 months, not responding to their name, losing skills they previously had, or showing no interest in social games like peekaboo.

12-24 Months: The Toddler Explosion

Development speeds up dramatically during the second year. Walking becomes running (usually badly, resulting in frequent falls). Climbing begins in earnest, making everything in your house suddenly dangerous.

Language explodes for most children. From a few words at 12 months to 50+ words and simple two-word phrases by 24 months is typical. Though again, some children don’t talk much until after age 2 and then suddenly acquire language rapidly.

They’re developing independence – wanting to do things themselves even when they clearly can’t, leading to epic meltdowns. This is cognitively and emotionally normal development, not behaviour problems.

Fine motor skills improve – they can stack blocks, scribble with crayons, use spoons (messily), and are obsessed with putting things into containers and dumping them out again.

Social development includes parallel play (playing alongside but not really with other children), showing affection to familiar people, and beginning pretend play.

Concerns at this age might include not walking by 18 months, fewer than 15 words by 18 months (or no words at all by 24 months), loss of previously acquired skills, no interest in pretend play, or lack of eye contact and social engagement.

2-3 Years: Preschool Skills Emerge

Two-year-olds are becoming more coordinated – jumping, kicking balls, running more smoothly. They can walk up and down stairs (though often still using both feet per step).

Language continues developing rapidly. By 3, most children speak in 3-4 word sentences that strangers can mostly understand, though pronunciation isn’t perfect. They’re learning colours, understanding concepts like “in” and “under,” and asking constant questions.

Pretend play becomes more complex – not just mimicking adult actions but creating scenarios. Social play starts emerging – actually playing with other children rather than just near them.

Emotionally, this is the infamous “terrible twos” period (which often extends into threes). Big feelings, limited emotional regulation skills, and growing independence create perfect storms of tantrums. Again, this is normal development, not dysfunction.

Fine motor skills allow them to turn pages individually, use crayons with more control, and start showing hand preference (though this can develop later too).

3-5 Years: Preschool And Beyond

These years involve refinement of existing skills and preparation for school. Physical abilities improve – they can hop on one foot, catch balls, ride tricycles, use scissors.

Language becomes quite sophisticated. They’re telling stories, using past and future tense (not always correctly), understanding most of what’s said to them, and speaking clearly enough for strangers to understand most of their speech.

Social skills develop rapidly – making friends, understanding social rules (though not always following them), engaging in cooperative play, showing empathy.

They’re developing early academic skills – recognising letters and numbers, understanding concepts like quantity and size, drawing recognisable pictures.

Emotional regulation improves (slowly). Tantrums become less frequent and intense as they develop better language to express frustration and more capacity to manage disappointment.

When To Actually Worry

Isolated delays in one area usually aren’t concerning if everything else is progressing normally. Children often focus on one developmental area at a time – some babies concentrate on physical skills and their language develops later, others do the opposite.

Concerning patterns include:

- Missing multiple milestones across different areas

- Losing skills they previously had

- Significant delays in all areas

- Not responding to sounds, voices, or their name

- No babbling by 12 months or no words by 18 months

- No pretend play by 2 years

- Very limited eye contact or social engagement

- Extreme rigidity about routines or activities

- Very floppy or very stiff muscle tone

Trust your instincts. If something feels off about your child’s development, it’s worth discussing with a health visitor, GP, or paediatrician even if you can’t articulate exactly what concerns you.

The Comparison Trap

Other parents will tell you when their children hit milestones – often the early ones, less often the late ones. This creates a skewed impression that all children walk at 10 months and speak in sentences at 18 months.

They don’t. You’re hearing about the early walkers and talkers because parents are excited about them. The children who walk at 15 months and don’t really talk until 2.5 years (both completely normal) aren’t being discussed at playgroups.

Resist the urge to compare constantly. Your child’s development isn’t a competition. The child who walks earliest isn’t destined for athletic greatness, and the child who talks late isn’t doomed to struggle academically.

Supporting Development Without Pushing

Children develop through play and everyday interactions, not through flash cards and formal teaching (at least not in early years).

Talking to your child constantly – narrating what you’re doing, reading books, singing songs – supports language development. Giving them opportunities to move – climbing, running, playing outside – supports physical development. Pretend play, puzzles, and building blocks support cognitive development.

You don’t need expensive educational toys or formal programmes. Household objects, cardboard boxes, water play, mud, and simple toys support learning perfectly well.

Following your child’s interests works better than pushing activities they’re not ready for or interested in. If they’re fascinated by vehicles, bring vehicles into everything – count toy cars, read books about trucks, pretend play with buses. They’ll learn more from engaged exploration of their interests than from activities you think are educational but they find boring.

Getting Help When Needed

If you’re concerned about your child’s development, speak up. Health visitors, GPs, and paediatricians can assess whether delays warrant further investigation or intervention.

Early intervention services exist for children showing developmental delays. Speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and various developmental support programmes can make significant differences when started early.

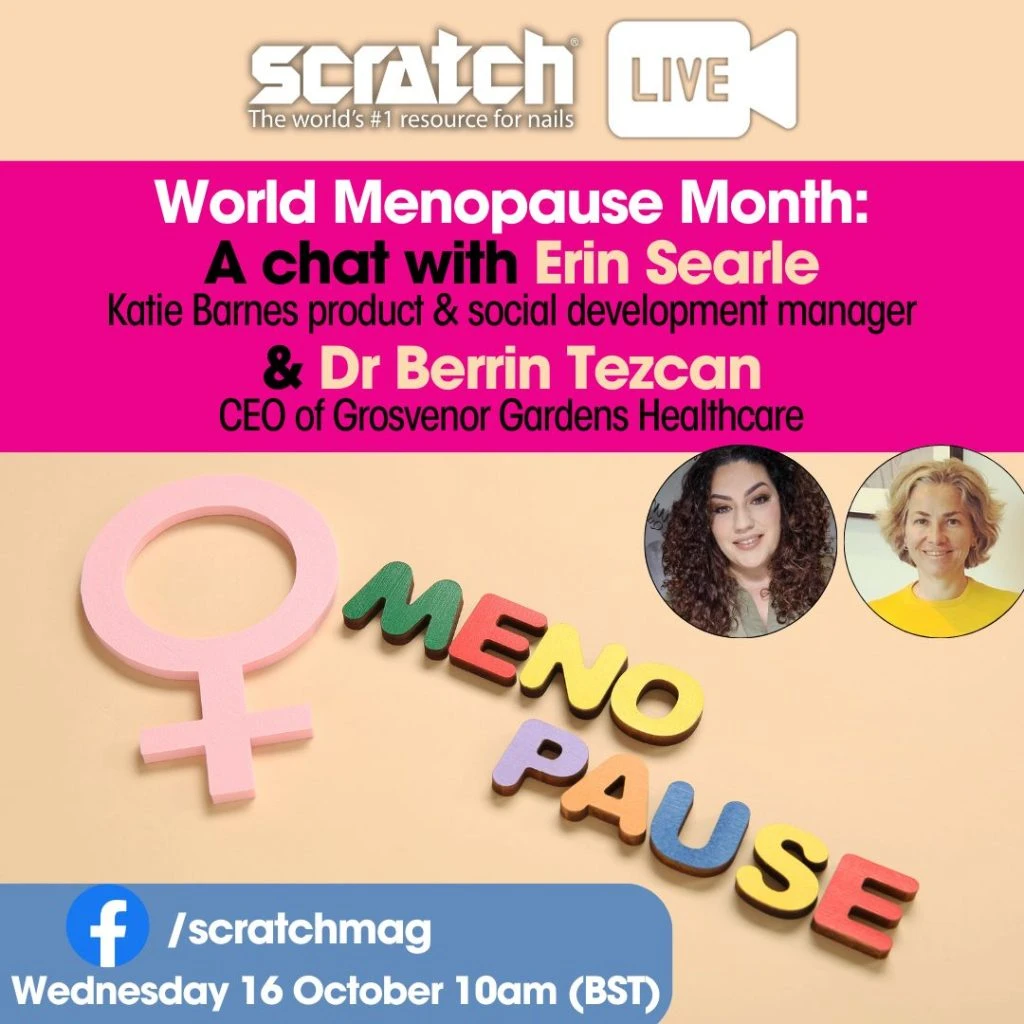

And if you’re looking for trusted doctors supporting child health needs, Grosvenor Gardens Healthcare provides thorough developmental assessments and can refer to specialist services when needed.

Don’t wait and see if delays resolve themselves if your concern persists beyond a few months. Sometimes they do resolve, but if intervention would help, starting earlier is almost always better.